Like a Pizza, or maybe a Theremin?

Re-Posting initial reflections on Kay and Goldberg’s “Personal Dynamic Media” for NMSF14

Double Creative Disruption Nugget

The internet’s disruptiveness is a consequence of its technical DNA. In programmers’ parlance, it’s a feature, not a bug – i.e. an intentional facility, not a mistake. And it’s difficult to see how we could disable the network’s facility for generating unpleasant surprises without also disabling the other forms of creativity it engenders. — John Naughton (2010)

My connected courses this semester have been full of unpleasant surprises of the technical kind. Many people of good will have tried to help coax overloaded servers back to the front lines. But without a warp drive we are all left peddling along.

Faster Captian Picard, faster!

Taking control would make things easier: We should lock down that platform, kick out those unruly widgets, limit the size, shape, and format of the content — for the sake of stability, for the sake of control, for the sake of the greater good. Right? Resistance is futile, right?

Not so slow!!!! Let’s not take away the flexibility that enables the creativity as well as the unpleasant surprises. Instead, let’s fix the warp drive so the Enterprise-internet can do what we made it to do, and what we do with it every time we engage it.

This nugget from John Naughton’s piece “Everything you need to know about the internet” highlights the yin and yang of creative disruption. In the seventies Vint Cerf and Robert Kahn sought to design a future-proof system that would link networks simply and seamlessly. They did that by setting up a decentralized net where no one person or entity has ownership or control and by embedding “neutrality” in the core architecture of the system. The network is simple in that it moves data packets from point to point. But it is neutral as to the content of those packets. So the same features that facilitate so many unpleasant surprises (malware, cyber stalking, incompatibilities) support the amazing, invigorating good stuff that brings us together and makes us smarter (communication, creation, augmentation, innovation).

Fencing off a little corner of the net as a kind of sandbox for students is a natural impulse. Locking things down will keep us safe, make things more efficient, and short circuit the frustration. But natural as it is, the impulse to exercise this kind of control thwarts the simple, empowering, free-range qualities that make the net the net and make the web a wonderfully flexible communication medium. The safe, impulse-drive installation would limit the unpleasant surprises, but it would also hamstring the creative potential that brings us here in the first place.

The disruption can be negative or positive, but it is embedded in the net’s DNA. Fiddling with that disruptive capability undercuts the whole enterprise. Disruption is a feature, not a bug.

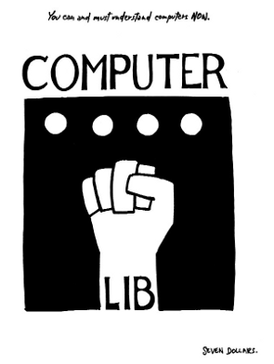

I need to understand that feature better in order to deal with the unpleasant surprises and cultivate more pleasant surprises. I need to take Ted Nelson’s injunction to heart:

“Computer Lib cover by Ted Nelson 1974” by Ted Nelson – The New Media Reader (2003), page 302. Licensed under Fair use via Wikipedia.

Because creativity requires facility, disruption enables innovation, and bugs in a web can be beautiful.

Oh, had I a golden thread

And a needle so fine

I’d weave a magic strand

Of rainbow design…..

Jeffrey on Steroids

The release of Walter Isaacson’s, The Innovators’ this week offers an ideal backdrop for tomorrow’s discussion of Doug Engelbart’s “Augmenting Human Intellect,” a text which in many ways serves as the animating heart of the New Media Seminar syllabus. Isaacson’s saga of the digital revolution — from its origins in the 1840s in the visions of Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage to the incorporation of Google — locates collaborative creativity as the engine driving the innovation that made the computer and the internet indispensable pieces of the global economy and social fabric. (See Matthew Wisnioski’s deft review in the Washington Post for the lowdown on this – better yet, read the book – I’m on the fence as to whether to Kindle this one or hold out for paper.) In any case, Isaacson’s shift away from the ineluctable preoccupation with lonely geniuses and transcendent individuals that shapes so many intellectual histories foregrounds a modality of innovation that Engelbart not only promoted, but considered essential to the project of leveraging “augmented” human intellects to address the world’s increasingly complex problems. (This post from last year talks about that a bit more.)

As good discussions often do, our encounter with Norbert Wiener and J. C. R. Licklider last week kept percolating with me long after we adjourned. One nugget I kept returning to was a conversation with the author of Icarus Falling. Just before the seminar began we empathized over the challenges of writing a reflective, substantive piece for a blog, and I admitted that I am still working against decades of training and discipline when it comes to getting my ideas formulated and expressed here. Historians tend to be solitary in their pursuits. We value rigor, depth and polish in our research and writing. Speed is not a common descriptor of our mode of production. I like to mull things over, draft, revise, go for a run, revise, repeat, repeat, repeat….And blogging, which is all about collaboration and creativity is just not compatible with those habits. And that is a good thing, in fact it is a great thing, but it is also a hard thing.

So, I was grateful when Anil Dash’s 15 Lessons from 15 Years of Blogging showed up in my Twitter feed. I can take something to heart from all 15 lessons — especially #9: Meta-writing about a blog is generally super boring.

(Ok. Enough of that then. Back to collaborative creativity as the innovative warp and intellectual weave of the web….)

Better encouragement came a couple days later in a student’s reflection that used the enlightening awe of a parent engaging a talented child to describe how blogging for our graduate historiography course has invigorated her work:

“So…Jeffrey, what do you think?”

This is actually a question that I ask often. Let me explain.

Jeffrey is my son and he often sees more sides to things than I do. I don’t actually remember exactly how old he was when I discovered this, but I remember thinking, “Wow, those are great ideas. I never thought of them.” Today, Jeffrey speaks three languages, holds degrees from Yale and Amherst and I continue to call him when in a quandary.

I say this not to be the ‘proud mama,’ but to explain what I think about our blogging activities. I think our blog page is like ‘Jeffrey on steroids.’ I can’t say that any one blogger influences me more than another. The corporate effort is really what illuminates ideas and impacts my thinking and writing.

She is wise and she is right. A published post joins the ecosystem of ideas, people, and information that make the web an augmenter of human intellect. In the reading, the writing, the commenting and the reflecting we engage each other in a transformative project that can help solve the world’s increasingly complex problems. I think Doug Engelbart would agree that “this” is indeed like Jeffrey (lots of Jeffries — and Sofias as well) on steriods (lots and lots of steriods.)

What kind of symbiosis?

Writing in the late 1950s, Norbert Wiener and J.C. R. Licklider both saw the future of computing as an interdependent relationship between people and computational machines. Wiener, founder of cybernetics, framed the information age as a second industrial revolution. The first had replaced the energy of humans and animals with that of steam engines. In the second, computers (machines) would become sources “of control and communication.” We would communicate with machines and machines would communicate with us and with each other. This worried Wiener, who feared that advances in automation would cause massive unemployment and our veneration of newly powerful computers might lead us to sacrifice our humanity to them. The latter concern grew from his understanding of computers as evolving entities “capable of learning.” Machines that could learn might quickly outpace their human masters, a haunting prospect that Wiener framed as a genie who could not be talked back into the bottle.(NMR, p. 72). Current studies of human-computer interaction suggest that his fears were not entirely unfounded.

Licklider also anticipated computers as new enablers of communication and problem solving, but was more sanguine about their relationship with humanity. Indeed he looked forward to a productive human-computer partnership, a relationship of interaction and interdependence he described as symbiosis.

I am struck by how both men invoked physiology and biology to explain computers. Wiener found them analogous to the nervous system and the homeostatic mechanisms that regulate bodily conditions and functions. As one might expect in the heyday of behaviorism, he described the nervous system in mechanistic terms, equating the firing of synapses to a binary switching operation in a computing machine. Licklider also invoked the nervous system in his vision for computers, but seemed more open to the creative possibilities presented by machines that would not only assist in problem solving, but also “facilitate formulative thinking.”

Computing machines can do readily, well, and rapidly many things that are difficult of impossible for man, and men can do readily and well, though not rapidly, many things that are difficult or impossible for computers. That suggests symbiotic cooperation, if successful in integrating the positive characteristics of men and computers, would be of great value. (NMR, p 77)

Biologists think about three kinds of symbiosis — mutualism, where both parties need each other; commensalism, where one partner benefits but has no effect on the other, and parasitism, where one party gains at the expense of the other. Licklider’s vision of symbiosis seems most closely aligned with the mutualist model, which is often invoked to describe the relationship between humans and dogs, or between clownfish and sea anenomes. For Wiener, parasitism offered the more powerful paradigm, and I doubt he found comfort knowing that even the nastiest parasites still need the host to survive. What I find most intriguing about all of this is the invocation of biological concepts that help us understand evolutionary relationships. Even if the machine is us(ing) us, it seems clear that we are in this together and changing each other along the way.